Many Dutch colonists grew affluent from the slave trade, building impressive colonial buildings in the capital of Willemstad; the city is now designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Landhouses (former plantation estates) and West African style kas di pal’i maishi (former slave dwellings) are scattered all over the island.

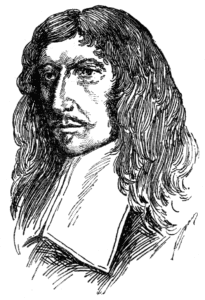

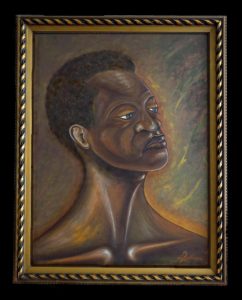

In 1795, a major slave revolt took place under the leaders Tula Rigaud, Louis Mercier, Bastian Karpata, and Pedro Wakao. Up to 4,000 slaves in northwest Curaçao revolted, with more than 1,000 taking part in extended gunfights. After a month, the slave owners suppressed the revolt.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, the British attacked the island several times, most notably in 1800, 1804, and from 1807 to 1815.

Stable Dutch rule returned in 1815 at the end of the Napoleonic wars, when the island was incorporated into the colony of Curaçao and Dependencies.

In the early 19th century, many Portuguese and Lebanese people migrated to Curaçao, attracted by the business opportunities.[citation needed]

The Dutch abolished slavery in 1863, bringing a change in the economy with the shift to wage labor.

Some inhabitants of Curaçao emigrated to other islands, such as Cuba, to work in sugarcane plantations. Other former slaves had nowhere to go and remained working for the plantation owner in the tenant farmer system. This was an instituted order in which a former slave leased land from his former master in exchange for promising to give up for rent most of his harvest. This system lasted until the beginning of the 20th century.

20th and 21st Centuries:

When oil was discovered in the Venezuelan Maracaibo Basin town of Mene Grande in 1914, Curaçao’s economy dramatically altered. In the early years, both Shell and Exxon held drilling concessions in Venezuela, which ensured a constant supply of crude oil to the refineries in Aruba and Curaçao.

In 1954 Curaçao was joined with the other Dutch colonies in the Caribbean into the Netherlands Antilles. Discontent with Curaçao’s seemingly subordinate relationship to the Netherlands and ongoing racial discrimination and a rise in unemployment owing to layoffs in the oil industry led to an outbreak of rioting in 1969. The riots resulted in two deaths, many injuries and severe damage to Willemstad. In response, the Dutch government introduced far-reaching reforms, allowing Afro-Curaçaoans greater influence in the islands’s political and economic life, and raising the prestige of the local language Papiamento.

Curaçao experienced an economic downturn in the early 1980s. Shell’s refinery there operated with significant losses from 1975 to 1979, and again from 1982 to 1985. Persistent losses, global overproduction, stronger competition, and low market expectations threatened the refinery’s future. In 1985, after 70 years, Royal Dutch Shell decided to end its activities on Curaçao.

In the mid-1980s, Shell sold the refinery for the symbolic amount of one Antillean guilder to a local government consortium. The aging refinery has been the subject of lawsuits in recent years, which charge that its emissions, including sulfur dioxide and particulate matter, far exceed safety standards. The government consortium leases the refinery to the Venezuelan state oil company PDVSA.