Other theories about the disappearance of the Norse settlement have been proposed;

- Lack of support from the homeland.

- Ship-borne marauders (such as Basque, English, or German pirates) rather than Skraelings, could have plundered and displaced the Greenlanders.

- They were “the victims of hidebound thinking and of a hierarchical society dominated by the Church and the biggest land owners. In their reluctance to see themselves as anything but Europeans, the Greenlanders failed to adopt the kind of apparel that the Inuit employed as protection against the cold and damp or to borrow any of the Eskimo hunting gear.”

- “Norse society’s structure created a conflict between the short-term interests of those in power, and the long-term interests of the society as a whole.”

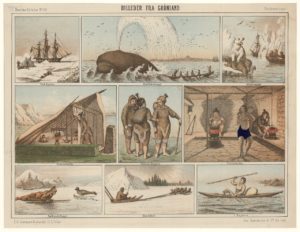

Thule Culture (1300–Present):

The Thule people are the ancestors of the current Greenlandic population. No genes from the Paleo-Eskimos have been found in the present population of Greenland. The Thule Culture migrated eastward from what is now known as Alaska around 1000, reaching Greenland around 1300. The Thule culture was the first to introduce to Greenland such technological innovations as dog sleds and toggling harpoons.

1500-1814:

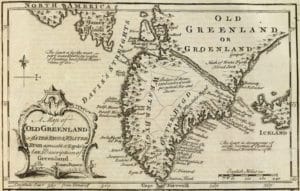

In 1500, King Manuel I of Portugal sent Gaspar Corte-Real to Greenland in search of a Northwest Passage to Asia which, according to the Treaty of Tordesillas, was part of Portugal’s sphere of influence. In 1501, Corte-Real returned with his brother, Miguel Corte-Real. Finding the sea frozen, they headed south and arrived in Labrador and Newfoundland. Upon the brothers’ return to Portugal, the cartographic information supplied by Corte-Real was incorporated into a new map of the world which was presented to Ercole I d’Este, Duke of Ferrara, by Alberto Cantino in 1502. The Cantino planisphere, made in Lisbon, accurately depicts the southern coastline of Greenland.

In 1605–1607, King Christian IV of Denmark sent a series of expeditions to Greenland and Arctic waterways to locate the lost eastern Norse settlement and assert Danish sovereignty over Greenland. The expeditions were mostly unsuccessful, partly due to leaders who lacked experience with the difficult arctic ice and weather conditions, and partly because the expedition leaders were given instructions to search for the Eastern Settlement on the east coast of Greenland just north of Cape Farewell, which is almost inaccessible due to southward drifting ice. The pilot on all three trips was English explorer James Hall.

After the Norse settlements died off, Greenland came under the de facto control of various Inuit groups, but the Danish government never forgot or relinquished the claims to Greenland that it had inherited from the Norse. When it re-established contact with Greenland in the early 17th century, Denmark asserted its sovereignty over the island. In 1721, a joint mercantile and clerical expedition led by Danish-Norwegian missionary Hans Egede was sent to Greenland, not knowing whether a Norse civilization remained there. This expedition is part of the Dano-Norwegian colonization of the Americas. After 15 years in Greenland, Hans Egede left his son Paul Egede in charge of the mission there and returned to Denmark, where he established a Greenland Seminary. This new colony was centered at Godthåb (“Good Hope”) on the southwest coast. Gradually, Greenland was opened up to Danish merchants, and closed to those from other countries.

Treaty of Kiel to World War II:

When the union between the crowns of Denmark and Norway was dissolved in 1814, the Treaty of Kiel severed Norway’s former colonies and left them under the control of the Danish monarch. Norway occupied then-uninhabited eastern Greenland as Erik the Red’s Land in July 1931, claiming that it constituted terra nullius. Norway and Denmark agreed to submit the matter in 1933 to the Permanent Court of International Justice, which decided against Norway.