In Slaves to Racism: An Unbroken Chain from America to Liberia, Benjamin Dennis and Anita Dennis argue that the Americo-Liberians replicated the only society most of them knew: the racist culture of the American South. Believing themselves different from and culturally and educationally superior to the indigenous peoples, the Americo-Liberians developed as an elite minority that held on to political power. They treated the natives the way American whites had treated them: as inferiors. The natives could not vote and could not speak unless spoken to. Just as people of color were prohibited from marrying white people in most of the United States, the indigenous Africans could not by law marry Americo-Liberians. Even when some indigenous Africans became educated in Western ways, they were broadly excluded from government positions. Indigenous tribesmen did not enjoy birthright citizenship in their own land until 1904. Americo-Liberians encouraged religious organizations to set up missions and schools to educate the indigenous peoples.

Independence:

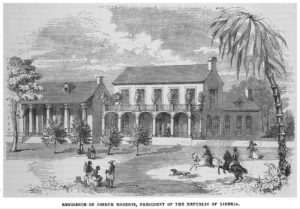

On July 26, 1847, the settlers issued a Declaration of Independence and promulgated a constitution. Based on the political principles of the United States Constitution, it established the independent Republic of Liberia. The United Kingdom was the first country to recognize Liberia’s independence. The United States did not recognize Liberia until 1862, after the southern states, who had significant influence in the American government, seceded from the union to form the Confederacy.

The leadership of the new nation consisted largely of the Americo-Liberians, who initially established political and economic dominance in the coastal areas that the ACS had purchased; they maintained relations with U.S. contacts in developing these areas and the resulting trade. Their passage of the 1865 Ports of Entry Act prohibited foreign commerce with the inland tribes, ostensibly to “encourage the growth of civilized values” before such trade was allowed in the region.

By 1877, the True Whig Party was the country’s most powerful political entity. It was made up primarily of Americo-Liberians, who maintained social, economic and political dominance well into the 20th century, repeating patterns of European colonists in other nations in Africa. Competition for office was usually contained within the party; a party nomination virtually ensured election.

Pressure from the United Kingdom, which controlled Sierra Leone to the northwest, and France, with its interests in the north and east, led to a loss of Liberia’s claims to extensive territories. Both Sierra Leone and the Ivory Coast annexed territories. Liberia struggled to attract investment to develop infrastructure and a larger, industrial economy.

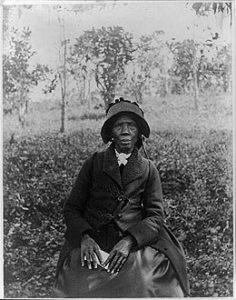

There was a decline in production of Liberian goods in the late 19th century, and the government struggled financially, resulting in indebtedness on a series of international loans. On July 16, 1892, Martha Ann Erskine Ricks met Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle and presented her a handmade quilt, Liberia’s first diplomatic gift. Born into slavery in Tennessee, Ricks said, “I had heard it often, from the time I was a child, how good the Queen had been to my people—to slaves—and how she wanted us to be free.”

Early 20th Century:

American and other international interests emphasized resource extraction, with rubber production a major industry in the early 20th century. In 1914 Imperial Germany accounted for three quarters of the trade of Liberia. This was a cause for concern among the British colonial authorities of Sierra Leone and the French colonial authorities of French Guinea and the Ivory Coast as tensions with Germany increased.