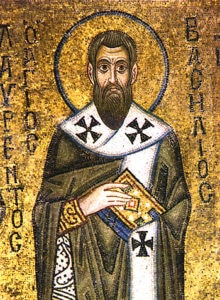

Under Byzantine rule, the island was divided into districts called mereíai (μερείαι) in Byzantine Greek, which were governed by a judge residing in Caralis and garrisoned by an army stationed in Forum Traiani (today Fordongianus) under the command of a dux. During this time, Christianity took deeper root on the island, supplanting the Paganism which had survived into the early Middle Ages in the culturally conservative hinterlands. Along with lay Christianity, the followers of monastic figures such as Basil of Caesarea became established in Sardinia.

While Christianity penetrated the majority of the population, the region of Barbagia remained largely pagan and, probably, partially non-Latin speaking. They re-established a short-lived independent domain with Sardinian-heathen lay and religious traditions, one of its kings being Hospito. Pope Gregory I wrote a letter to Hospito defining him “Dux Barbaricinorum” and, being Christian, the leader and best of his people. In this unique letter about Hospito, the Pope prompts him to convert his people who “living all like irrational animals, ignore the true God and worship wood and stone”.

The dates and circumstances of the end of Byzantine rule in Sardinia are not known. Direct central control was maintained at least through c. 650, after which local legates were empowered in the face of the rebellion of Gregory the Patrician, Exarch of Africa and the first invasion of the Muslim conquest of the Maghreb. There is some evidence that senior Byzantine administration in the Exarchate of Africa retreated to Caralis following the final fall of Carthage to the Arabs in 697. The loss of imperial control in Africa led to escalating raids by Moors and Berbers on the island, the first of which is documented in 705, forcing increased military self-reliance in the province. Communication with the central government became daunting if not impossible during and after the Muslim conquest of Sicily between 827 and 902. A letter by Pope Nicholas I as early as 864 mentions the “Sardinian judges”, without reference to the empire and a letter by Pope John VIII (reigned 872–882) refers to them as principes (“princes”).

By the time of De Administrando Imperio, completed in 952, the Byzantine authorities no longer listed Sardinia as an imperial province, suggesting they considered it lost. In all likelihood a local noble family, the Lacon-Gunale, acceded to the power of Archon, still identifying themselves as vassals of the Byzantines, but de facto independent as communications with Constantinople were very difficult. We know only two names of those rulers, Salusios and the protospatharios Turcoturios from two inscriptions, who probably reigned between the 10th and the 11th century. These rulers were still closely linked to the Byzantines, both for a pact of ancient vassalage, and from the ideological point of view, with the use of the Byzantine Greek language (in a Romance country), and the use of art of Byzantine inspiration.

In the early 11th century, an attempt to conquer the island was made by the Moors based in the Iberian Peninsula. The only records of that war are from Pisan and Genoese chronicles. The Christians won, but after that, the previous Sardinian kingdom was totally undermined and divided into four small states: Cagliari (Calari), Arborea (Arbaree), Gallura, Torres or Logudoro.