Beginning in the sixth century, the area that is now Scotland was divided into three areas: Pictland, a patchwork of small lordships in central Scotland; the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Northumbria, which had conquered southeastern Scotland; and Dál Riata, founded by settlers from Ireland, bringing Gaelic language and culture with them. These societies were based on the family unit and had sharp divisions in wealth, although the vast majority were poor and worked full-time in subsistence agriculture. The Picts kept slaves (mostly captured in war) through the ninth century.

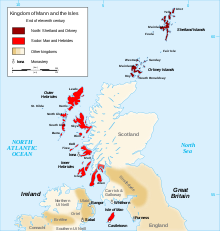

Gaelic influence over Pictland and Northumbria was facilitated by the large number of Gaelic-speaking clerics working as missionaries. Operating in the sixth century on the island of Iona, Saint Columba was one of the earliest and best-known missionaries. The Vikings began to raid Scotland in the eighth century. Although the raiders sought slaves and luxury items, their main motivation was to acquire land. The oldest Norse settlements were in northwest Scotland, but they eventually conquered many areas along the coast. Old Norse entirely displaced Gaelic in the Northern Isles.

In the ninth century, the Norse threat allowed a Gael named Cináed mac Ailpín (Kenneth I) to seize power over Pictland, establishing a royal dynasty to which the modern monarchs trace their lineage, and marking the beginning of the end of Pictish culture. The kingdom of Cináed and his descendants, called Alba, was Gaelic in character but existed on the same area as Pictland. By the end of the tenth century, the Pictish language went extinct as its speakers shifted to Gaelic. From a base in eastern Scotland north of the River Forth and south of the River Spey, the kingdom expanded first southwards, into the former Northumbrian lands, and northwards into Moray. Around the turn of the millennium, there was a centralization in agricultural lands and the first towns began to be established.