The Natives’ Land Act of 1913 severely restricted the ownership of land by blacks; at that stage they controlled only seven percent of the country. The amount of land reserved for indigenous peoples was later marginally increased.

In 1931, the union was fully sovereign from the United Kingdom with the passage of the Statute of Westminster, which abolished the last powers of the Parliament of the United Kingdom to legislate on the country. In 1934, the South African Party and National Party merged to form the United Party, seeking reconciliation between Afrikaners and English-speaking whites. In 1939, the party split over the entry of the Union into World War II as an ally of the United Kingdom, a move which the National Party followers strongly opposed.

Beginning of Apartheid:

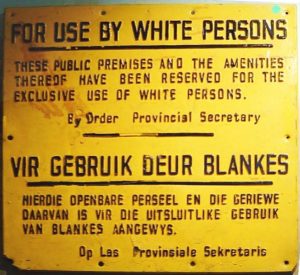

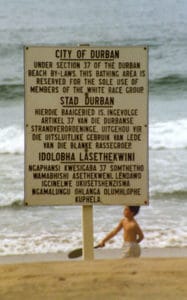

In 1948, the National Party was elected to power. It strengthened the racial segregation begun under Dutch and British colonial rule. Taking Canada’s Indian Act as a framework, the nationalist government classified all peoples into three races and developed rights and limitations for each. The white minority (less than 20%) controlled the vastly larger black majority. The legally institutionalized segregation became known as apartheid.

While whites enjoyed the highest standard of living in all of Africa, comparable to First World Western nations, the black majority remained disadvantaged by almost every standard, including income, education, housing, and life expectancy. The Freedom Charter, adopted in 1955 by the Congress Alliance, demanded a non-racial society and an end to discrimination.

Republic:

On 31 May 1961, the country became a republic following a referendum (only open to white voters) which narrowly passed; the British-dominated Natal province largely voted against the proposal. Queen Elizabeth II lost the title Queen of South Africa, and the last Governor-General, Charles Robberts Swart, became State President. As a concession to the Westminster system, the appointment of the president remained an appointment by parliament, and virtually powerless until P. W. Botha’s Constitution Act of 1983, which eliminated the office of Prime Minister and instated a near-unique “strong presidency” responsible to parliament. Pressured by other Commonwealth of Nations countries, South Africa withdrew from the organization in 1961 and rejoined it only in 1994.

Despite opposition both within and outside the country, the government legislated for a continuation of apartheid. The security forces cracked down on internal dissent, and violence became widespread, with anti-apartheid organizations such as the African National Congress (ANC), the Azanian People’s Organisation (AZAPO), and the Pan-Africanist Congress (PAC) carrying out guerrilla warfare and urban sabotage. The three rival resistance movements also engaged in occasional inter-factional clashes as they jockeyed for domestic influence. Apartheid became increasingly controversial, and several countries began to boycott business with the South African government because of its racial policies. These measures were later extended to international sanctions and the divestment of holdings by foreign investors.

In the late 1970s, South Africa initiated a program of nuclear weapons development. In the following decade, it produced six deliverable nuclear weapons.

End of Apartheid:

The Mahlabatini Declaration of Faith, signed by Mangosuthu Buthelezi and Harry Schwarz in 1974, enshrined the principles of peaceful transition of power and equality for all, the first of such agreements by black and white political leaders in South Africa. Ultimately, FW de Klerk opened bilateral discussions with Nelson Mandela in 1993 for a transition of policies and government.