In 1600, the Polish-Swedish War broke out, causing further devastation. The protracted war ended in 1629 with Sweden gaining Livonia, including the regions of Southern Estonia and Northern Latvia. Danish Saaremaa was transferred to Sweden in 1645. The wars had halved the Estonian population from about 250–270,000 people in the mid 16th century to 115–120,000 in the 1630s.

While serfdom was retained under Swedish rule, legal reforms took place which strengthened peasants’ land usage and inheritance rights, resulting this period’s reputation of the “Good Old Swedish Time” in people’s historical memory. Swedish king Gustaf II Adolf established gymnasiums in Reval and Dorpat; the latter was upgraded to Tartu University in 1632. Printing presses were also established in both towns. In the 1680s the beginnings of Estonian elementary education appeared, largely due to efforts of Bengt Gottfried Forselius, who also introduced orthographical reforms to written Estonian. The population of Estonia grew rapidly for a 60–70-year period, until the Great Famine of 1695–97 in which some 70,000–75,000 people perished – about 20% of the population.

Russian Era and National Awakening:

In 1700, the Great Northern War started, and by 1710 the whole of Estonia was conquered by the Russian Empire. The war again devastated the population of Estonia, with the 1712 population estimated at only 150,000–170,000. Russian administration restored all the political and landholding rights of Baltic Germans. The rights of Estonian peasants reached their lowest point, as serfdom completely dominated agricultural relations during the 18th century. Serfdom was formally abolished in 1816–1819, but this initially had very little practical effect; major improvements in rights of the peasantry started with reforms in the mid-19th century.

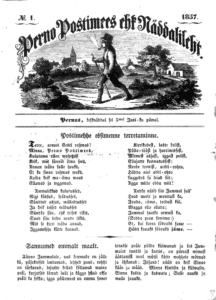

The Estonian national awakening began in the 1850s as the leading figures started promoting an Estonian national identity among the general populace. Its economic basis was formed by widespread farm buyouts by peasants, forming a class of Estonian landowners. In 1857 Johann Voldemar Jannsen started publishing the first Estonian language newspaper and began popularizing the denomination of oneself as eestlane (Estonian).

Schoolmaster Carl Robert Jakobson and clergyman Jakob Hurt became leading figures in a national movement, encouraging Estonian peasants to take pride in themselves and in their ethnic identity. The first nationwide movements formed, such as a campaign to establish the Estonian language Alexander School, the founding of the Society of Estonian Literati and the Estonian Students’ Society, and the first national song festival, held in 1869 in Tartu. Linguistic reforms helped to develop the Estonian language. The national epic Kalevipoeg was published in 1862, and 1870 saw the first performances of Estonian theatre. In 1878 a major split happened in the national movement. The moderate wing led by Hurt focused on development of culture and Estonian education, while the radical wing led by Jacobson started demanding increased political and economical rights.

In the late 19th century the Russification period started, as the central government initiated various administrative and cultural measures to tie Baltic governorates more closely to the empire. The Russian language was used throughout the education system and many Estonian social and cultural activities were suppressed. Still, some administrative changes aimed at reducing power of Baltic German institutions did prove useful to Estonians. In the late 1890s there was a new surge of nationalism with the rise of prominent figures like Jaan Tõnisson and Konstantin Päts. In the early 20th century Estonians started taking over control of local governments in towns from Germans.