From the seventh century CE, the Srivijaya naval kingdom flourished as a result of trade and the influences of Hinduism and Buddhism. Between the eighth and tenth centuries CE, the agricultural Buddhist Sailendra and Hindu Mataram dynasties thrived and declined in inland Java, leaving grand religious monuments such as Sailendra’s Borobudur and Mataram’s Prambanan. The Hindu Majapahit kingdom was founded in eastern Java in the late 13th century, and under Gajah Mada, its influence stretched over much of present-day Indonesia. This period is often referred to as a “Golden Age” in Indonesian history.

The earliest evidence of Islamized populations in the archipelago dates to the 13th century in northern Sumatra. Other parts of the archipelago gradually adopted Islam, and it was the dominant religion in Java and Sumatra by the end of the 16th century. For the most part, Islam overlaid and mixed with existing cultural and religious influences, which shaped the predominant form of Islam in Indonesia, particularly in Java.

Colonial Era:

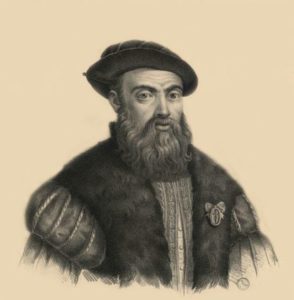

The first Europeans arrived in the archipelago in 1512, when Portuguese traders, led by Francisco Serrão, sought to monopolize the sources of nutmeg, cloves, and cubeb pepper in the Maluku Islands.

Dutch and British traders followed. In 1602, the Dutch established the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and became the dominant European power for almost 200 years. The VOC was dissolved in 1800 following bankruptcy, and the Netherlands established the Dutch East Indies as a nationalized colony.

For most of the colonial period, Dutch control over the archipelago was tenuous. Dutch forces were engaged continuously in quelling rebellions both on and off Java. The influence of local leaders such as Prince Diponegoro in central Java, Imam Bonjol in central Sumatra, Pattimura in Maluku, and bloody 30-year war in Aceh weakened the Dutch and tied up the colonial military forces. Only in the early 20th century did their dominance extend to what was to become Indonesia’s current boundaries.

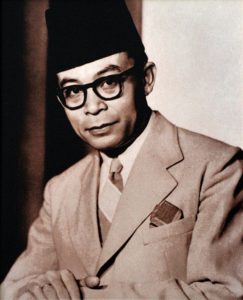

The Japanese invasion and subsequent occupation during World War II ended Dutch rule and encouraged the previously suppressed independence movement. Two days after the surrender of Japan in August 1945, Sukarno and Mohammad Hatta, influential nationalist leaders, proclaimed Indonesian independence and were appointed president and vice-president respectively.

The Netherlands attempted to re-establish their rule, and a bitter armed and diplomatic struggle ended in December 1949 when the Dutch formally recognized Indonesian independence in the face of international pressure. Despite extraordinary political, social and sectarian divisions, Indonesians, on the whole, found unity in their fight for independence.

Modern Era:

As president, Sukarno moved Indonesia from democracy towards authoritarianism and maintained power by balancing the opposing forces of the military, political Islam, and the increasingly powerful Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI). Tensions between the military and the PKI culminated in an attempted coup in 1965. The army, led by Major General Suharto, countered by instigating a violent anti-communist purge that killed between 500,000 and one million people. The PKI was blamed for the coup and effectively destroyed. Suharto capitalized on Sukarno’s weakened position, and following a drawn-out power play with Sukarno, Suharto was appointed president in March 1968. His “New Order” administration, supported by the United States, encouraged foreign direct investment, which was a crucial factor in the subsequent three decades of substantial economic growth.