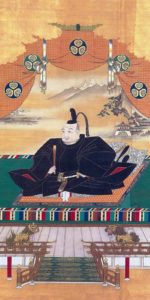

Tokugawa Ieyasu served as regent for Hideyoshi’s son Toyotomi Hideyori and used his position to gain political and military support. When open war broke out, Ieyasu defeated rival clans in the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600. He was appointed shōgun by Emperor Go-Yōzei in 1603 and established the Tokugawa shogunate at Edo (modern Tokyo).

The shogunate enacted measures including buke shohatto, as a code of conduct to control the autonomous daimyōs, and in 1639 the isolationist sakoku (“closed country”) policy that spanned the two and a half centuries of tenuous political unity known as the Edo period (1603–1868). Modern Japan’s economic growth began in this period, resulting in roads and water transportation routes, as well as financial instruments such as futures contracts, banking and insurance of the Osaka rice brokers. The study of Western sciences (rangaku) continued through contact with the Dutch enclave at Dejima in Nagasaki. The Edo period also gave rise to kokugaku (“national studies”), the study of Japan by the Japanese.

Modern Era:

In 1854, Commodore Matthew Perry and the “Black Ships” of the United States Navy forced the opening of Japan to the outside world with the Convention of Kanagawa. Similar treaties with Western countries in the Bakumatsu period brought economic and political crises. The resignation of the shōgun led to the Boshin War and the establishment of a centralized state nominally unified under the emperor (the Meiji Restoration).

Adopting Western political, judicial, and military institutions, the Cabinet organized the Privy Council, introduced the Meiji Constitution, and assembled the Imperial Diet. During the Meiji era (1868–1912), the Empire of Japan emerged as the most developed nation in Asia and as an industrialized world power that pursued military conflict to expand its sphere of influence. Starting with consolidation of its borders to the north and south via the Hokkaidō Development Commission and so-called Ryūkyū Disposition, after victories in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895) and the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905), Japan gained control of Taiwan, Korea and the southern half of Sakhalin. The Japanese population doubled from 35 million in 1873 to 70 million by 1935.

The early 20th century saw a period of Taishō democracy (1912–1926) overshadowed by increasing expansionism and militarization. World War I allowed Japan, which joined the side of the victorious Allies, to capture German possessions in the Pacific and in China. The 1920s saw a political shift towards statism, the passing of laws against political dissent, and a series of attempted coups. This process accelerated during the 1930s, spawning a number of Radical Nationalist groups that shared a hostility to liberal democracy and a dedication to expansion in Asia. In 1931, Japan invaded and occupied Manchuria; following international condemnation of the occupation, it resigned from the League of Nations two years later. In 1936, Japan signed the Anti-Comintern Pact with Nazi Germany; the 1940 Tripartite Pact made it one of the Axis Powers.

The Empire of Japan invaded other parts of China in 1937, precipitating the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945). In 1940, the Empire invaded French Indochina, after which the United States placed an oil embargo on Japan. On December 7–8, 1941, Japanese forces carried out surprise attacks on Pearl Harbor, as well as on British forces in Malaya, Singapore, and Hong Kong, and declared war on the United States and the British Empire, beginning World War II in the Pacific.