New nationalist movements appeared in Bosnia by the middle of the 19th century. Bolstered by Serbia’s breakaway from the Ottoman Empire in the early 19th century, Serbian nationalists began making contacts and sending nationalist propaganda claiming Bosnia as a Serbian province. In the neighboring Habsburg Empire across the Ottoman border, Croatian nationalists made similar claims about Bosnia as a Croatian province. The rise of these competing movements marked the beginning of nationalist politics in Bosnia, which continued to grow in the rest of the 19th and 20th centuries.

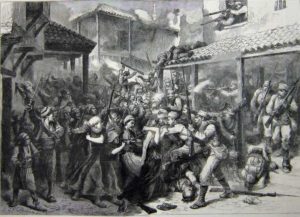

Agrarian unrest eventually sparked the Herzegovinian rebellion, a widespread peasant uprising, in 1875. The conflict rapidly spread and came to involve several Balkan states and Great Powers, a situation that led to the Congress of Berlin and the Treaty of Berlin in 1878.

Austro-Hungarian Rule (1878–1918):

At the Congress of Berlin in 1878, the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister Gyula Andrássy obtained the occupation and administration of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and he also obtained the right to station garrisons in the Sanjak of Novi Pazar, which remained under Ottoman administration until 1908, when the Austro-Hungarian troops withdrew from the Sanjak.

Although Austro-Hungarian officials quickly came to an agreement with Bosnians, tensions remained and a mass emigration of Bosnians occurred. However, a state of relative stability was reached soon enough and Austro-Hungarian authorities were able to embark on a number of social and administrative reforms they intended would make Bosnia and Herzegovina into a “model” colony.

Habsburg rule had several key concerns in Bosnia. It tried to dissipate the South Slav nationalism by disputing the earlier Serb and Croat claims to Bosnia and encouraging identification of Bosnian or Bosniak identity. Habsburg rule also tried to provide for modernisation by codifying laws, introducing new political institutions, and establishing and expanding industries.

Austria–Hungary began to plan annexation of Bosnia, but due to international disputes the issue was not resolved until the annexation crisis of 1908. Several external matters affected status of Bosnia and its relationship with Austria–Hungary. A bloody coup occurred in Serbia in 1903, which brought a radical anti-Austrian government into power in Belgrade. Then in 1908, the revolt in the Ottoman Empire raised concerns the Istanbul government might seek the outright return of Bosnia-Herzegovina. These factors caused the Austro-Hungarian government to seek a permanent resolution of the Bosnian question sooner, rather than later.

Taking advantage of turmoil in the Ottoman Empire, Austro-Hungarian diplomacy tried to obtain provisional Russian approval for changes over the status of Bosnia Herzegovina and published the annexation proclamation on 6 October 1908. Despite international objections to the Austro-Hungarian annexation, Russians and their client state, Serbia, were compelled to accept the Austrian-Hungarian annexation of Bosnia Herzegovina in March 1909.

In 1910, Habsburg Emperor Franz Joseph proclaimed the first constitution in Bosnia, which led to relaxation of earlier laws, elections and formation of the Bosnian parliament, and growth of new political life.

On 28 June 1914, a Yugoslav nationalist youth named Gavrilo Princip, a member of the secret Serbian-supported movement, Young Bosnia, assassinated the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, in Sarajevo—an event that was the spark that set off World War I. At the end of the war, the Bosniaks had lost more men per capita than any other ethnic group in the Habsburg Empire whilst serving in the Bosnian-Herzegovinian Infantry (known as Bosniaken) of the Austro-Hungarian Army. Nonetheless, Bosnia and Herzegovina as a whole managed to escape the conflict relatively unscathed.