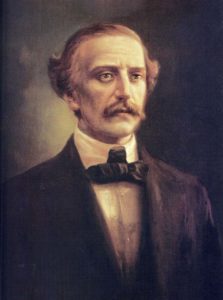

On February 27, 1844, the surviving members of La Trinitaria declared the independence from Haiti. They were backed by Pedro Santana, a wealthy cattle rancher from El Seibo, who became general of the army of the nascent republic. The Dominican Republic’s first Constitution was adopted on November 6, 1844, and was modeled after the United States Constitution. The decades that followed were filled with tyranny, factionalism, economic difficulties, rapid changes of government, and exile for political opponents. Archrivals Santana and Buenaventura Báez held power most of the time, both ruling arbitrarily. They promoted competing plans to annex the new nation to another power: Santana favored Spain, and Báez the United States.

Threatening the nation’s independence were renewed Haitian invasions. On 19 March 1844, the Haitian Army, under the personal command of President Hérard, invaded the eastern province from the north and progressed as far as Santiago, but was soon forced to withdraw after suffering disproportionate losses. According to José María Imbert’s (the General defending Santiago) report of April 5, 1844 to Santo Domingo, “in Santiago, the enemy did not leave behind in the battlefield less than six hundred dead and…the number of wounded was very superior…[while on] our part we suffered not one casualty.”

The Dominicans repelled the Haitian forces, on both land and sea, by December 1845. The Haitians invaded again in 1849 after France recognized the Dominican Republic as an independent nation. In an overwhelming onslaught, the Haitians seized one frontier town after another. Santana being called upon to assume command of the troops, met the enemy at Ocoa, April 21, 1849, with only 400 men, and succeeded in utterly defeating the Haitian army. In November 1849 Báez launched a naval offensive against Haiti to forestall the threat of another invasion. His seamen under the French adventurer, Fagalde, raided the Haitian coasts, plundered seaside villages, as far as Cape Dame Marie, and butchered crews of captured enemy ships. In 1855, Haiti invaded again, but its forces were repulsed at the bloodiest clashes in the history of the Dominican–Haitian wars, the Battle of Santomé in December 1855 and the Battle of Sabana Larga in January 1856.

First Republic:

The Dominican Republic’s first constitution was adopted on November 6, 1844. The state was commonly known as Santo Domingo in English until the early 20th century. It featured a presidential form of government with many liberal tendencies, but it was marred by Article 210, imposed by Pedro Santana on the constitutional assembly by force, giving him the privileges of a dictatorship until the war of independence was over. These privileges not only served him to win the war but also allowed him to persecute, execute and drive into exile his political opponents, among which Duarte was the most important. In Haiti after the fall of Boyer, black leaders had ascended to the power once enjoyed exclusively by the mulatto elite.

Without adequate roads, the regions of the Dominican Republic developed in isolation from one another. In the south, also known at the time as Ozama, the economy was dominated by cattle-ranching (particularly in the southeastern savannah) and cutting mahogany and other hardwoods for export. This region retained a semi-feudal character, with little commercial agriculture, the hacienda as the dominant social unit, and the majority of the population living at a subsistence level. In the north (better-known as Cibao), the nation’s richest farmland, peasants supplemented their subsistence crops by growing tobacco for export, mainly to Germany. Tobacco required less land than cattle ranching and was mainly grown by smallholders, who relied on itinerant traders to transport their crops to Puerto Plata and Monte Cristi. Santana antagonized the Cibao farmers, enriching himself and his supporters at their expense by resorting to multiple peso printings that allowed him to buy their crops for a fraction of their value. In 1848, he was forced to resign and was succeeded by his vice-president, Manuel Jimenes.