In subsequent years, the insurgency was near collapse, but in 1820 Viceroy Juan Ruiz de Apodaca sent an army under the criollo general Agustín de Iturbide against the troops of Vicente Guerrero who had among his trusted soldiers, Filipino Mexicans who were concentrated in Guerrero, a state later named after Vicente Guerrero himself and where the Mexican flag was first sewn. Chief among the Filipino-Mexican soldiers was General Isidoro Montes de Oca who defeated Royalist armies 3 times his force’s size. Then, the Criollo Royalist, Agustin Iturbide, instead of attacking Vicente Guerrero, approached Guerrero to join forces as he was impressed with his tenacity despite fighting larger odds, and on 24 August 1821 representatives of the Spanish Crown and Iturbide signed the “Treaty of Córdoba” and the “Declaration of Independence of the Mexican Empire“, which recognized the independence of Mexico under the terms of the “Plan of Iguala“. Similarly to José María Morelos’ goals. A provision of the Plan of Iguala of Agustín de Iturbide bringing about Mexican independence in 1821, also included Catholic exclusivity in the religious sphere. The Constitution of 1824 declared that the official religion of the Republic would be Catholic.

Mexico’s short recovery after the War of Independence was soon cut short again by the civil wars, foreign invasion and occupation, and institutional instability of the mid-19th century, which lasted until the government of Porfirio Díaz reestablished conditions that paved the way for economic growth. The conflicts that arose from the mid-1850s had a profound effect because they were widespread and made themselves perceptible in the vast rural areas of the countries, involved clashes between castes, different ethnic groups, and haciendas, and entailed a deepening of the political and ideological divisions between republicans and monarchists.

Mexican Empire and the Early Republic (1821–1855):

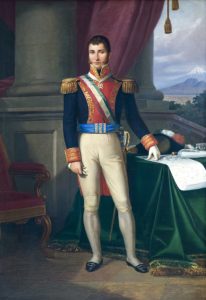

The first thirty-five years after Mexico’s independence were marked by political instability and the changing form of the Mexican State, from a monarchy to a federated republic. There were military coups d’état, foreign invasions, ideological conflict between Conservatives and Liberals, and economic stagnation. Catholicism remained the only permitted religious faith and the Catholic Church as an institution retained its special privileges, prestige, and property, a bulwark of Conservatism. The army, another Conservative institution, also retained its privileges. Former Royal Army General Agustín de Iturbide, became regent, as newly independent Mexico sought a constitutional monarch from Europe. When no member of a European royal house desired the position, Iturbide himself was declared Emperor Agustín I. The young and weak United States was the first country to recognize Mexico’s independence, sending an ambassador to the court of the emperor and sending a message to Europe via the Monroe Doctrine not to intervene in Mexico.

The emperor’s rule was short (1822–23) and he was overthrown by army officers.

The successful rebels established the First Mexican Republic. In 1824, a constitution of a federated republic was promulgated and former insurgent general Guadalupe Victoria became the first president of the newly born republic. Central America, including Chiapas, left the union. In 1829, former insurgent general and fierce Liberal Vicente Guerrero, a signatory of the Plan de Iguala that achieved independence, became president in a disputed election. During his short term in office, April to December 1829, he abolished slavery. As a visibly mixed-race man of modest origins, Guerrero was seen by white political elites as an interloper. His Conservative vice president, former Royalist General Anastasio Bustamante, led a coup against him and Guerrero was judicially murdered. There was constant strife between Liberals, supporters of a federal form of decentralized government and often called Federalists and their political rivals, the Conservatives, who proposed a hierarchical form of government, were termed Centralists.